Food Processing Unit Cost Calculator

Estimate Your Processing Unit Costs

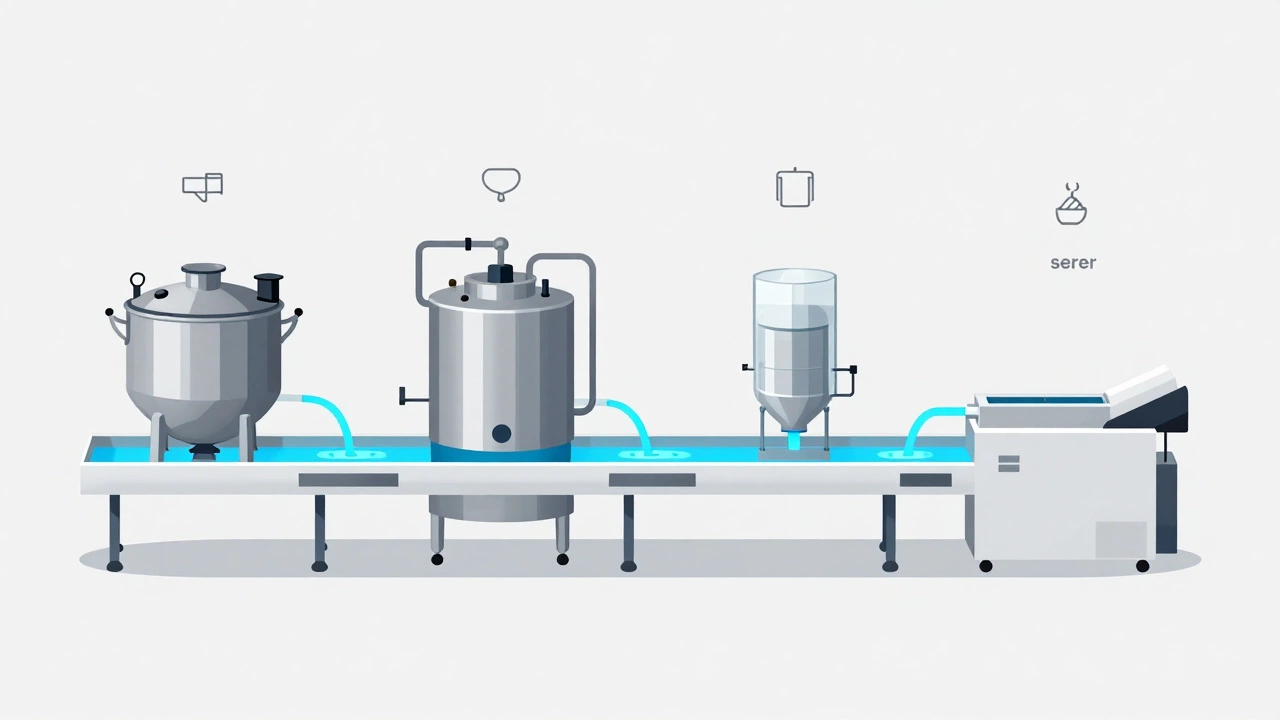

When you hear the term processing unit, you might think of a computer’s CPU. But in food manufacturing, it means something completely different - and it’s the heart of every small or large food production line. The processing unit in food production is also known as a food processing machine or food line equipment. It’s not one single device. It’s a system - a chain of machines working together to turn raw ingredients into packaged food products you find on grocery shelves.

What Exactly Is a Food Processing Unit?

A food processing unit isn’t a gadget you buy off Amazon. It’s a custom-built setup designed for a specific task: cleaning, cutting, cooking, mixing, packaging, or preserving food. Think of it like a kitchen on steroids. Instead of one person chopping onions and boiling sauce, a food processing unit does that at 500 times the speed, with consistent quality and zero human error.

For example, a unit making canned tomato sauce might include:

- A conveyor belt that feeds whole tomatoes into a washer

- A steam peeler that removes skins in seconds

- A pulper that crushes tomatoes into puree

- A pasteurizer that heats the sauce to kill bacteria

- A filler that pours the sauce into cans

- A sealer and labeler that finishes the product

All these parts are linked together - that’s the processing unit. It’s not just the machine you see; it’s the entire workflow.

Why Do People Call It a Processing Unit?

The term “processing unit” comes from engineering and manufacturing jargon. In any industry, a unit is a self-contained system that performs a defined function. In food, it’s the part of the factory that actually changes the food - from raw to ready-to-sell.

People in the industry avoid saying “machine” because one unit can have ten different machines working as one. Saying “processing unit” makes it clear you’re talking about the whole operation, not just a single part. It’s like calling a car an “engine” - technically wrong, but people know what you mean.

Smaller businesses, like local jam makers or artisanal cheese producers, often refer to their single machine as a “processing unit” too - even if it’s just a mixer and filler. In their world, that one machine does the core job of transforming ingredients. So the term is flexible, but always tied to transformation, not just handling.

Common Names for Food Processing Units

Depending on where you are or what you’re making, you’ll hear different names for the same thing:

- Food processing machine - used by small manufacturers and equipment sellers

- Food line equipment - common in technical manuals and factory blueprints

- Production line - used by managers and plant supervisors

- Processing line - popular in export documentation and international trade

- Food processing system - often used in government grants and startup funding applications

There’s no official standard, but if you’re buying equipment or applying for a permit, you’ll need to know these terms. Local health inspectors might ask for your “processing unit specifications,” while your supplier might call it a “food line setup.”

How Big Can a Processing Unit Get?

Processing units range from the size of a kitchen counter to entire warehouse floors.

At the small end, you’ve got a single stainless steel unit that does everything for a family-run pickle business: washes cucumbers, slices them, mixes brine, fills jars, and seals them. This unit might cost $8,000 and fit in a 10x10 foot room.

At the large end, companies like Nestlé or PepsiCo run processing units that span 50,000 square feet. These include robotic arms, AI-driven quality cameras, automated palletizers, and real-time sanitation monitoring systems. These units can process 10,000 liters of juice per hour - all without a single person touching the product after it enters the system.

The scale doesn’t change what it is - just how complex it becomes. Even the biggest unit still follows the same basic principle: input → process → output.

What Makes a Good Processing Unit?

Not all processing units are built the same. A good one doesn’t just work - it works reliably, safely, and efficiently. Here’s what matters:

- Food-grade materials - everything that touches food must be stainless steel 316 or FDA-approved plastic. No rust, no leaching, no hidden crevices where bacteria can hide.

- Easy to clean - CIP (Clean-in-Place) systems are standard in modern units. No disassembly. Just push a button and hot water, detergent, and sanitizer flow through the pipes.

- Modular design - if you want to add a new step later (like adding a protein powder mix), you shouldn’t need to rebuild the whole line.

- Compliance - must meet local food safety rules (like FDA in the U.S., CFIA in Canada, or FSSAI in India). Inspectors check for this before you even start production.

- Energy efficiency - modern units use variable-speed drives and heat recovery systems to cut electricity use by 30-50% compared to older models.

One manufacturer in Ontario told me they switched from a 1990s unit to a new modular system. Their downtime dropped from 14 hours a week to under 2. Their waste went from 12% to 3%. That’s not just convenience - that’s profit.

What Happens If You Skip the Right Processing Unit?

Skipping a proper processing unit - or using a DIY setup - is a recipe for disaster.

In 2023, a small yogurt producer in British Columbia got shut down after an E. coli outbreak. Their “processing unit” was a hand-mixed vat, a manual filler, and a fridge. No pasteurizer. No sanitation logs. No testing. The health department found the same bacteria in their product and their sink.

Even if you don’t get sick, you’ll lose money. Poorly designed units cause:

- Product waste from inconsistent filling

- Slow output that misses delivery deadlines

- High maintenance costs from broken parts

- Rejection by retailers who demand certified equipment

There’s no shortcut. If you’re making food for sale, your processing unit isn’t an expense - it’s your license to operate.

Where Are Processing Units Made?

Most small and mid-sized food processing units in North America come from manufacturers in Canada, the U.S., Germany, Italy, and China. Canadian companies like FoodTech Systems in Ontario or Agri-Matic in Quebec specialize in units for dairy, meat, and produce. They’re popular because they meet CFIA standards and are built for cold climates.

Chinese manufacturers offer lower prices, but you often pay later in maintenance or compliance issues. German and Italian units are expensive but last 20+ years and are designed for high hygiene standards - ideal for export markets.

Many startups start with used equipment. A refurbished pasta extruder from Italy might cost $15,000 instead of $50,000 new. Just make sure it’s been inspected, cleaned, and certified for food use.

How Do You Choose the Right One?

Here’s a simple checklist to follow:

- What food are you making? (Liquid? Solid? Frozen? Shelf-stable?)

- How much do you need to produce per day? (50 kg? 500 kg? 5,000 kg?)

- Do you need automation? (Manual loading? Semi-auto? Full robot line?)

- What’s your budget? (Include installation, training, and 1 year of maintenance)

- Will you export? (Then you need HACCP, ISO 22000, or FDA compliance)

Don’t buy the biggest unit you can afford. Buy the one that fits your volume and product. A unit too big wastes energy. One too small becomes a bottleneck.

Ask for a live demo. Watch them run your exact product through it. If the vendor can’t do that, walk away.

What’s Next for Food Processing Units?

By 2026, processing units are getting smarter. AI now predicts when a belt will slip or a valve will clog - before it happens. Sensors monitor pH, temperature, and viscosity in real time. Some units even auto-adjust recipes based on ingredient quality.

Small businesses are now leasing units instead of buying them. Companies like ProcessFlow Rentals in Toronto let you rent a full pasta line for $1,200 a month - no upfront cost. You pay only for the hours you use.

There’s also a push for smaller, modular units that can fit in a shipping container. This lets food makers set up production in remote areas or pop-up markets. A unit that turns local grains into flour or beans into protein bars can now be shipped and installed in a weekend.

Technology is making processing units more accessible - but the core idea hasn’t changed. It’s still about turning raw food into safe, consistent, sellable products. That’s why the name matters: it’s not a machine. It’s a processing unit - the brain and muscle of modern food production.

Is a food processing unit the same as a food processor?

No. A food processor is a small kitchen appliance - like a Cuisinart - used for chopping or blending small amounts of food at home. A food processing unit is an industrial system that handles hundreds or thousands of kilograms per hour. They serve completely different purposes.

Can I build my own food processing unit?

Technically, yes - but legally, it’s risky. Most countries require food equipment to be certified for food contact and sanitation. DIY setups rarely meet these standards. Even if your product is safe, retailers and inspectors will reject it. It’s cheaper and safer to buy or lease a certified unit.

Do all food processing units need electricity?

Almost all do. Even manual systems - like hand-cranked meat grinders - are rare in commercial settings because they’re too slow and inconsistent. Electric motors power conveyors, pumps, heaters, and sealers. Some small units use compressed air, but electricity is the standard.

How long does a food processing unit last?

A well-maintained unit lasts 15 to 25 years. Stainless steel parts can last decades. Motors and sensors may need replacing every 5-10 years. The key is regular cleaning and scheduled maintenance. Units that are neglected fail faster - sometimes in under 5 years.

Are used food processing units safe to buy?

Yes, if they’ve been properly refurbished. Look for sellers who provide cleaning logs, part replacements, and certification from a food safety inspector. Avoid units that smell like old oil or have rust spots. Ask for a video of the unit running your product before you pay.